Chicago’s Well-being – The Incarcerated

Info Advanced Studio, Professor Piergianna Mazzocca

Team Gable Bostic, Research with Juan Acosta

Date Fall 2019

Research

The initial half of this studio consisted of a research assignment where students were asked to define and identify architectural and urban types described as public forms of health in the context of Chicago. The goal was to methodically dissect and ultimately connect similarities between spatial relationships and the systems that govern them through the collection of documents that speak of their creation and how they have been historically constructed. The assemblage of this information and the creation of a catalog served as a critical instrument to inform our design intervention for the remainder of the studio.

Correctional

Facilities.

Gable Bostic

Juan Acosta

Juan Acosta

1 Eastern State Pen Hallway

1 Eastern State Pen HallwayThe criminal justice system in the United States is failing the incarcerated and by extension is compromising public health. The current attitudes of how we treat the prisoners and the design of the spaces in which they are incarcerated have a long reaching historical basis, but there is evidence that the current system of mass incarceration is not working or, rather, is working too well. Policies that have focused on stopping crime versus helping people have led to the United States having the largest incarcerated population in the world. The city of Chicago is an ideal lens through which to understand this issue. Here, as in the rest of the county, people of color and those suffering through mental health and substance abuse have been disproportionately affected by these punitive measures. In fact, rather than releasing reformed and functioning individuals, the commodification of the prisoner population has led to bloated expenses for the state and is returning the formerly incarcerated unprepared for re-assimilation into their communities. Through understanding specific examples in the city, we hope to study the past present and future of prisoner health and the differences between the architecture of punishment and the architecture of reform.

THE CARCERAL STATE: A HISTORY

The first jail in the history of Chicago was an “estray pen” built in 1832 in the town square at the intersection of Randolph and Clark street. By 1852 the basement jail in the new Cook County courthouse was the first brick and mortar building for incarceration. This was the state of developments for much of the United States, where “frontier justice” was fast acting, leaving no need for large centers of incarceration1. However, as populations grew and cities matured there was a need for substantial institutional buildings for long term incarceration.

Jeremy Bentham’s Panopticon, and the power dynamics created by positioning a single all seeing inspector at the center of radially organized cells that housed inmates that could not see the inspector in return, was foundational for the design of many institutions such as hospitals, mental asylums, and prisons around the world. Eastern State Penitentiary is an early example of a prison that was formally influenced by the Panoptican in conjunction with the ideals of the Quakers that founded it. Here, eight wings of cells radiate out from a central control tower. This wheel and spoke plan is inscribed in a square shaped perimeter wall. Theology manifest itself in the church-like vaulted corridors, the short height of the cell doors that forced inmates to bow as they left and entered their cells, and the single glass skylight inside them that carried religious symbolism. The idea of penance was also present in how the inmates were

The first jail in the history of Chicago was an “estray pen” built in 1832 in the town square at the intersection of Randolph and Clark street. By 1852 the basement jail in the new Cook County courthouse was the first brick and mortar building for incarceration. This was the state of developments for much of the United States, where “frontier justice” was fast acting, leaving no need for large centers of incarceration1. However, as populations grew and cities matured there was a need for substantial institutional buildings for long term incarceration.

Jeremy Bentham’s Panopticon, and the power dynamics created by positioning a single all seeing inspector at the center of radially organized cells that housed inmates that could not see the inspector in return, was foundational for the design of many institutions such as hospitals, mental asylums, and prisons around the world. Eastern State Penitentiary is an early example of a prison that was formally influenced by the Panoptican in conjunction with the ideals of the Quakers that founded it. Here, eight wings of cells radiate out from a central control tower. This wheel and spoke plan is inscribed in a square shaped perimeter wall. Theology manifest itself in the church-like vaulted corridors, the short height of the cell doors that forced inmates to bow as they left and entered their cells, and the single glass skylight inside them that carried religious symbolism. The idea of penance was also present in how the inmates were

Eastern State Penitentiary

Eastern State Penitentiaryreprimanded; an innovation commonly known today as solitary confinement. Auburn Correctional Facility in New York state, was another early nineteenth century institution that was ideologically the opposite of Eastern State Penitentiary and was more widely adopted20. Instead of a reformatory approach, the prison operated under the Auburn System which was characterized by striped uniforms, lockstep, silence, and hard labor. It became the first prison in the United States that profited from the labor it compelled prisoners to perform.

2 Eastern State Pen Cel

The era of mass incarceration that we know today can be said to have begun in the mid to late twentieth century where a series of policy changes, both intentional agendas and folly, have compounded to create a prison population that grew by 500 percent in 30 years3. This era is defined by a shift from rehabilitation to punitive action. In the sixties, President Lyndon B Johnson initiated social welfare programs via his Great Society that ultimately overfunded policing and prisons and failed to live up to its promises of reform. Arguably this contributed to the social environment that resulted in the Watts Riots in 1965, the Detroit Riots of 1967, and a general climate of civil unrest. This situation was exacerbated by the Nixon administration’s Tough on Crime campaign11. Indeterminate sentencing was put in place premised on the idea that individualized sentences in each case and on rehabilitation as the primary aim for punishment. The result, however, was that it allowed undue leniency in some situations and overly strict sentencing in others. Undoubtedly, one of the most significant contributors to the current condition is the War on Drugs initiated in the Ronald Reagan Era where government distinctly shifted from an approach contingent on rehabilitation to a punitive system. Policies such as mandatory minimum, three strikes, and truth-in-sentencing laws contributed to a higher incarceration rate, especially in minority communities. In 1950, 70 percent of those behind bars were white, by 1990, the ratio had flipped: 70 percent were African American and Latino2. This racial bias and disparity in incarceration is particularly evident in sentencing for crack cocaine and cocaine in powdered form. An almost one hundred to one ratio in time sentenced between the drugs unequally targeted African American communities where the cheaper derivative of the same drug was most popular and overlooked white communities dispute higher usage statistics.

1950

1990

White - 70%

African American &

Latino - 30%

African American &

Latino - 70%

White - 30%

Changes in Inmate Demographics

Changes in Inmate Demographics

“You want to know what this was really all about...The Nixon campaign in 1968, and the Nixon White House after that, had two enemies: the antiwar left and black people. You understand what I’m saying. We knew we couldn’t make it illegal to be either against the war or black, but by getting the public to associate the hippies with marijuana and blacks with heroin, and then criminalizing both heavily, we could disrupt those communities. We could arrest their leaders, raid their homes, break up their meetings, and vilify them night after night on the evening news. Did we know we were lying about the drugs? Of course we did.”

- John Ehrlec

Domestic Policy Chief for President Nixon

Domestic Policy Chief for President Nixon

The subsequent administrations can be clustered into a “period of drift” where policies did not shift substantially one way or another. Today there has been at least acknowledgement of the failures of the criminal justice system. Most recently, the First Step Act of 2018 which gives deserving prisoners the opportunity to get a shortened sentence for positive behavior and job training, and gives judges and juries the power that the Constitution intended to grant them in sentencing1. However, the Federal Bureau of Prisons has seen a rotating cast of individuals at its helm. The criminal justice apparatus has bloated in cost along every scale of government. According to the Federal Bureau of Prisons it costs $36,299.25 annually to detain a single inmate6. Additionally, at the state level in 1987, states spent $10.6 billion on corrections. By 2008, that figure had risen to $47 billion4. Despite this growing expense, there is a growing trend of government cutting funding for mental health services.

Illinois, for one, cut $113.7 million in general revenue funding for mental health services from 2009-2012. These were some of the largest cuts in mental health funding nationwide during this time4. Given that 60% of incarcerated individuals nationwide meet diagnostic criteria for mental illness and that it can cost three times as much to jail someone with a mental illness4 the significance is that there are fewer mental health services left for fewer people. Unfortunately, the Federal Bureau of Prisons imposed new policies promising better care and oversight for inmates with mental health issues while simultaneously raising the threshold to qualify for regular treatment17. The FBP classifies 3% of inmates in this category while California, New York, and Texas recognize 30%, 21%, and 20% respectively17. Those with mental health issues are also less likely to succeed in prison system. This is sobering considering the high recidivism rate for the general population. In the eyes of the law, the mental health of inmates is not a priority.

![]() Map of Selected Buildings of Significance

Map of Selected Buildings of Significance

Ultimately, the consequence is a carceral state that has disproportionately entrapped people of color and failed those with psychology and mental health issues. Chicago is emblematic of the consequences of this system. Since 1940 the Chicago city jail system and the Cook County jail system have merged into one entity making Cook County Jail today the largest single site jail in the country and simultaneously one of the largest national healthcare providers as well3. As in the rest of the country, many of those entering the system do so because of mental health and substance abuse issues. In Illinois, 68 percent of those imprisoned are African American, and of the drug offenders who are returning to Chicago after release, 92 percent are African American2. This fact is representative of the intersection of race and substance abuse and mental health at play in the community. These people ultimately return home with little options due to lack of education/job training. There is an opportunity to improve the overall health of the city if we address the issues plaguing these marginalized communities. Instead of prioritizing preemptive treatment to keep these people out of the incarceration system, the state currently provides treatment retroactively if at all.

Illinois, for one, cut $113.7 million in general revenue funding for mental health services from 2009-2012. These were some of the largest cuts in mental health funding nationwide during this time4. Given that 60% of incarcerated individuals nationwide meet diagnostic criteria for mental illness and that it can cost three times as much to jail someone with a mental illness4 the significance is that there are fewer mental health services left for fewer people. Unfortunately, the Federal Bureau of Prisons imposed new policies promising better care and oversight for inmates with mental health issues while simultaneously raising the threshold to qualify for regular treatment17. The FBP classifies 3% of inmates in this category while California, New York, and Texas recognize 30%, 21%, and 20% respectively17. Those with mental health issues are also less likely to succeed in prison system. This is sobering considering the high recidivism rate for the general population. In the eyes of the law, the mental health of inmates is not a priority.

Map of Selected Buildings of Significance

Map of Selected Buildings of SignificanceUltimately, the consequence is a carceral state that has disproportionately entrapped people of color and failed those with psychology and mental health issues. Chicago is emblematic of the consequences of this system. Since 1940 the Chicago city jail system and the Cook County jail system have merged into one entity making Cook County Jail today the largest single site jail in the country and simultaneously one of the largest national healthcare providers as well3. As in the rest of the country, many of those entering the system do so because of mental health and substance abuse issues. In Illinois, 68 percent of those imprisoned are African American, and of the drug offenders who are returning to Chicago after release, 92 percent are African American2. This fact is representative of the intersection of race and substance abuse and mental health at play in the community. These people ultimately return home with little options due to lack of education/job training. There is an opportunity to improve the overall health of the city if we address the issues plaguing these marginalized communities. Instead of prioritizing preemptive treatment to keep these people out of the incarceration system, the state currently provides treatment retroactively if at all.

3 Joliet Prison

3 Joliet PrisonTHE CARCERAL TYPOLOGY

THE FORTRESS : Old Joliet Prison, located in Joliet, Illinois, 45 miles southwest of Chicago, received its first prisoners on May 22, 1858. It replaced Illinois’ first penitentiary, Alton Military Prison. Originally, all that stood was a small castellated gothic structure designed by one of Chicago’s earliest architects, W. W. Boyington, architect of the Chicago Water Tower. Inmates, leased by the state to contractor Lorenzo P. Sanger and warden Samuel K. Casey, immediately got to work mining limestone from local quarries to finish construction of the remaining buildings and walls, inclosing a 16-acre yard, that can be found there today21. The original plans included a one-hundred cell “female cell house” adjacent to the men’s cells. These female prisoners were housed there from 1859 to 1870 when they were moved to the fourth floor of the central administration building. In 1896, a female specific facility, called “Joliet Women’s Prison,” was built across the street from Old Joliet Prison, modeled as an exact replica of the original structure. Finally, in 1933, all female inmates were moved to a separate facility and male prisoners were moved into this structure22.

Joliet Prison

Joliet PrisonThis “fortress” style prison consisted of two mirrored cell blocks on each side of a central administration building. Each cell block is a two-story structure with an opening connecting the two levels. Each level has 46 cells, with two prisoners per cell. Conditions were abysmal to say the least. Originally intended to house 1,800 inmates, the prison swelled to 2,000 by 1878. Running water and toilets were not added to the buildings until 1910. Before then, prisoners bathed once a week in the summer and once every two weeks in the winter in the prison’s 15 iron tubs. With so few tubs, prisoners were forced to share tubs to expedite the process. A dining hall was not built until 1903, forcing inmates to eat in their shared 4’x7’ cells prior to that. By 1915, prisoners were allowed one hour of daily outdoor recreation. Reports of these unsanitary and unacceptable conditions were reported as early as 1905 and calls for its closure were made. Despite these calls for closure, Old Joliet remained open until 200221.

Old Joliet Prison is a prime example of punitive prison architecture. Housing some of society’s most violent offenders, there was little desire to treat those who were confined there with humanity. It was pushed to the peripheries of greater Chicago in an attempt to further separate the inmates from those of the general population. As a result, the chances of reformation were made exponentially more challenging.

Cook County Jail

Cook County JailCITY STATE : Cook County Jail is located 7.5 miles southwest of downtown Chicago, but still within the limits of the city. The jail, which we have labeled a “city state” takes up 96 acres, consists of 11 separate divisions and is the largest single site jail in the United States. The majority of the housing units that make up Cook County Jail are arranged in what is known as a “telephone pole” design. This design includes a central corridor with housing wings built at 90 degrees off the corridor. These numerous structures house anywhere from 9,000 to 11,000 inmates, employs 3900 law enforcement officials and 7000 civilian employees. The facility processes around 100,000 people through it each year. Before it grew to the size it is today, the jail consisted of smaller jails spread throughout the area. In the mid-to-late-1800s, suspects awaiting trial for serious crimes were held at the site of the Cook County Criminal Court Building on Hubbard Street in a jail attached to the courthouse. Another jail known a “Bridewell” housed less serious offenders. These two facilities were moved to the current site of Cook County Jail in the mid-1900s and soon gained the reputation as the “largest concentration of inmates in the free world”23.

5 Cook County Jail Sleeping Quarters

“Since 1940 the Chicago city jail system and the Cook County jail system have merged into one entity making Cook County Jail today the largest single site jail in the country and simultaneously one of the largest national healthcare providers as well. As in the rest of the country, many of those entering the system do so because of mental health and substance abuse issues.”

“In Illinois, 68 percent of those imprisoned are African American, and of the drug offenders who are returning to Chicago after release, 92 percent are African American...These people ultimately return home with little options due to lack of education/job training.”

In July 2008, the civil rights division of the United States Department of Justice released a report finding that the Eighth Amendment civil rights of the inmates, that prohibits the federal government from imposing excessive bail, excessive fines, or cruel and unusual punishments, had been systematically violated. The report found that the jail failed to provide adequate medical and mental health care; failed to provide adequate suicide prevention; failed to provide adequate sanitary environmental conditions; failed to adequately protect inmates from harm or risk of harm from other inmates or staff; failed to provide adequate fire safety precautions. This is particularly troubling since Cook County Jail is considered one of the largest providers of healthcare in the country. A conservative estimate of inmates in Cook County Jail that have some form of mental illness is 1 in 3.

Cook County Jail is the archetype of the current United States correctional system as a whole. Plagued with issues including overcrowding, aging facilities or poor to nonexistent healthcare available to the inmates, you don’t have to look anywhere else to see how our policies from the last few decades are failing those who need the most help. Approaches to solve some of the biggest challenges we face when it comes to prison reform can be gleaned from a deep investigation into this facility.

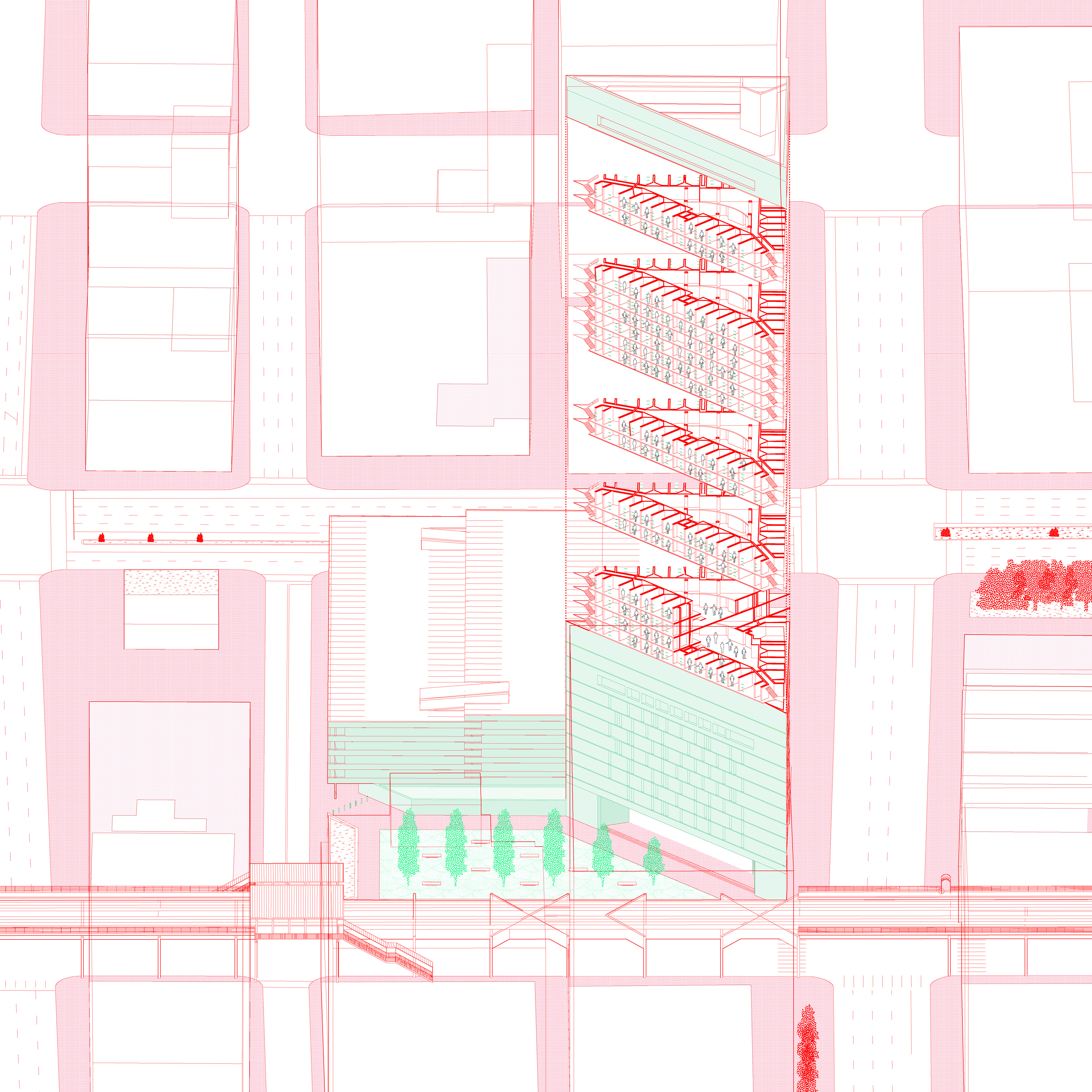

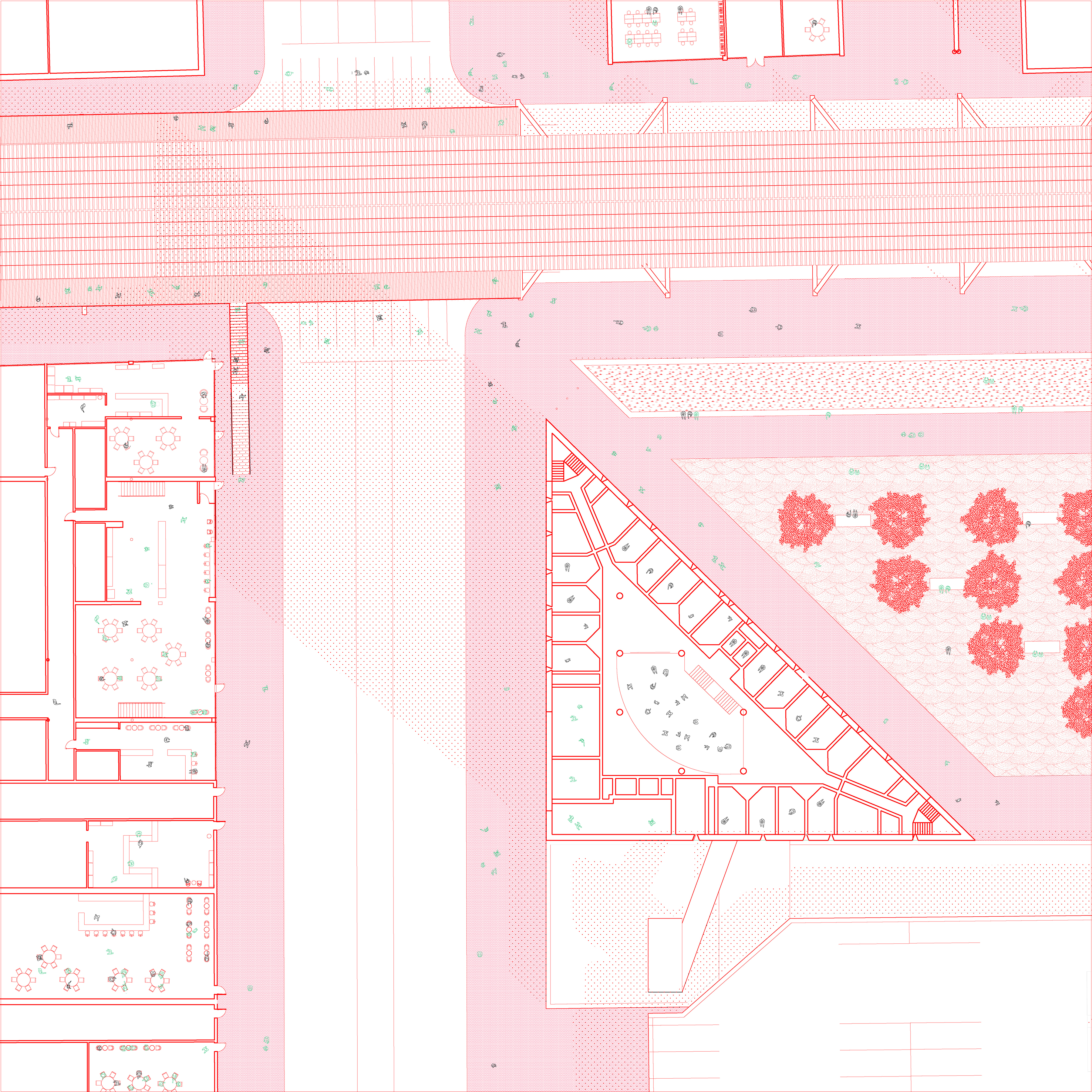

MCC Chicago

MCC ChicagoTOWER : The Federal Bureau of Prisons announced their plans to construct 66 new correctional facilities starting in 1968 in response to higher crime rates, increased prison crowding and riots. The Metropolitan Correctional Center in Chicago, or MCC for short, was one of these facilities included in the Federal program. Presented as a demonstration project, this minimum-security facility was to offer more humane conditions for inmates. Despite this, the building drew a fierce backlash as soon as its downtown location of Clark and Van Buren was announced. A group of banks and civic organizations located within the loop of Chicago filed a lawsuit to kill the project fearing it would drive away business and reduce property values. The suit was eventually thrown out, but it exemplified the public’s perception of jails and those housed within them.

Harry Weese & Associates were selected to design the MCC of Chicago in 1972. With them, they brought their modernist ideals that architects had a moral imperative to ease social ills. The subsequent design was a striking 27-story tower employing simple geometric forms, ubiquitous to the work from the firm. The triangular plan of the tower creates an illusion of a two-dimensional plane, reducing the visual mass of the structure. The façade is constructed of slip-form cast concrete with slit windows arranged randomly, creating a pattern of sorts. The width of the windows was determined by the maximum allowable width of 5 inches determined by the Bureau of Prisons. Eventually, bars were added on the interior following a successful escape in 1985. These design decisions were an attempt to design a jail that would be decent for the detained and an appealing addition to the loop24.

MCC Chicago

MCC ChicagoDesigned to house 440 inmates, the jail is separated into self-contained modules of 44 people. Each module consists of two floors with single-room cells arranged around the perimeter of the plan. A double height common area is at the center with a guard station that allows clear views to all cells in the module. This was modeled after Jeremy Bentham’s Panopticon prison design. A yard located on the roof of the building give inmates access to the outdoors.

The Metropolitan Correctional Center is an interesting new approach to housing our incarcerated. With a focus on less crowded units with individual cells and access to more natural light, the right steps were taken to offer a more humane approach to incarceration. Also, the central location of the facility makes it easier for families to visit their loved ones serving time. This allows for stronger connections between the two, enabling quicker assimilation back into the general public.

INVESTIGATION THROUGH DELINEATION

Map of Chicago with “L” train, average household income per neighborhood (dense green being the highest), and number of citizens serving time per neighborhood (dense red being the highest).

Map of Chicago with “L” train, average household income per neighborhood (dense green being the highest), and number of citizens serving time per neighborhood (dense red being the highest). Facade study - Relationship between the Chicago MCC (Metropolitan Correctional

Center) with its urban setting.

Facade study - Relationship between the Chicago MCC (Metropolitan Correctional

Center) with its urban setting. MCC Organization Diagram

MCC Organization Diagram  MCC’s

relationship with

immediate context.

MCC’s

relationship with

immediate context.Go to Design

ENDNOTES

1. “The FIRST STEP Act: What & Why” RED - Stop Recidivism, March 20, 2019. https://stoprecidivism.org/the-first-step-act-what-why/?gclid=CjwKCAjwk93rBRBLEiwAcMapUXMNamunVZn6TGgp1F6UxdEInDRKSs_kYko4wI4FenDowGODnYUKxoCqBEQA

2. “An End to Mass Incarceration: University of Chicago.” SSA, January 1, 1970. https://ssa.uchicago.edu/ssa_magazine/end-mass-incarceration

3. Michaels, Samantha. “Chicago’s Jail Is One of the Country’s Biggest Mental Health Care Providers. Here’s a Look inside.” Mother Jones, January 11, 2019.

https://www.motherjones.com/crime-justice/2019/01/chicagos-jail-is-the-one-of-the-countys-biggest-mental-health-care-providers-heres-a-look-inside/

4. “Making the Case for Funding and Supporting Comprehensive, Evidence-Based Mental Health Services in Illinois.” illinoishealthmatter.org. NAMI Chicago, May 2015

5. “Black Holes of Architecture.” Chicago Underground Practice. Accessed September 19, 2019. http://www.chicagoundergroundpractice.com/black-holes-of-architecture.html

6. “Annual Determination of Average Cost of Incarceration.” Federal Register, April 30, 2018

7. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2018/04/30/2018-09062/annual-determination-of-average-cost-of-incarceration

8. “Cook County Jail’s History.” Cook County Sheriffs. Accessed September 19, 2019. https://www.cookcountysheriff.org/cook-county-department-of-corrections/cook-county-jails-history/

9. “Economic Perspectives on Incarceration and the Criminal Justice System: Executive Summary (Excerpted).” Federal Sentencing Reporter 28, no. 5 (January 2016): 361–62. https://doi.org/10.1525/fsr.2016.28.5.361

10 “COLLATERAL COSTS: Incarcerations Effect on Economic Mobility.” Accessed September 19, 2019. https://www.pewtrusts.org/~/media/legacy/uploadedfiles/pcs_assets/2010/collateralcosts1pdf.pdf

11. Travis, Jeremy, and Bruce Western. The Growth of Incarceration in the United States: Exploring Causes and Consequences. Washington, D.C.: The National Academies Press, 2014

12. James, Doris J., and Lauren E. Glaze. “Mental Health Problems of Prison and Jail Inmates.” PsycEXTRA Dataset, 2006. https://doi.org/10.1037/e557002006-001

13. “The Growth of Incarceration in the United States: Exploring Causes and Consequences.” Choice Reviews Online 52, no. 05 (2014). https://doi.org/10.5860/choice.185911.

14. John, Arit. “A Timeline of the Rise and Fall of ‘Tough on Crime’ Drug Sentencing.” The Atlantic. Atlantic Media Company, April 22, 2014. https://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2014/04/a-timeline-of-the-rise-and-fall-of-tough-on-crime-drug-sentencing/360983/

15. “Prison Health Care Costs and Quality.” The Pew Charitable Trusts. Accessed

September 12, 2019. https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/reports/2017/10/prison-health-care-costs-and-quality/target="_blank">www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/reports/2017/10/prison-health-care-costs-and-quality

16. September 12, 2019. https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/reports/2017/10/prison-health-care-costs-and-quality

17. Thompson, Christie. “Why So Few Federal Prisoners Get The Mental Health Care They Need.” The Marshall Project. The Marshall Project, November 21, 2018. https://www.themarshallproject.org/2018/11/21/treatment-denied-the-mental-health-crisis-in-federal-prisons.

18. “Top Adviser to Richard Nixon Admitted That ‘War on Drugs’ Was Policy Tool to Go After Anti-War Protesters and ‘Black People’.” Drug Policy Alliance. Accessed September 20, 2019. http://www.drugpolicy.org/press-release/2016/03/top-adviser-richard-nixon-admitted-war-drugs-was-policy-tool-go-after-anti

19. “Cracks in the System: 20 Years of the Unjust Federal Crack Cocaine Law.”

American Civil Liberties Union. Accessed September 20, 2019. https://www.aclu.org/other/cracks-system-20-years-unjust-federal-crack-cocaine-law

20. Barber, Judson. Interviewed by Juan Acosta

September 11th, 2019

21. “Timeline.” Old Joliet Prison. Accessed September 20, 2019. https://www.jolietprison.org/timeline/

22. Dodge, L. Mara. “Whores and Thieves of the Worst Kind” a Study of Women, Crime, and Prisons, 1835-2000. DeKalb: Northern Illinois University Press, 2006

23. “Cook County Jail’s History.” Cook County Sheriffs. Accessed September 19, 2019. https://www.cookcountysheriff.org/cook-county-department-of-corrections/cook-county-jails-history/

IMAGE CREDITS

1. Eastern State Pen Hallway -

“Timeline.” Eastern State Penitentiary Historic Site. Accessed September 20, 2019. https://www.easternstate.org/research/history-eastern-state/timeline

2. Eastern State Pen Cell -

“Eastern State Penitentiary.” Flashbak. Accessed September 20, 2019. https://flashbak.com/benjamin-franklin-forced-enlightenment-on-isolated-prisoners-inside-the-worlds-first-penitentiary-364464/12-cassidys-book-two-inmates-in-a-cell/

3. Joliet Prison Exterior -

Katelyn Oprondek Special to the Daily Journal. “Exhibit Explores What’s to Be Done with the Old Joliet Prison.” The Daily Journal, November 19, 2016. https://www.daily-journal.com/news/local/exhibit-explores-what-s-to-be-done-with-the-old/article_a4f34ffb-ea62-567d-86d9-7d2e257c336f.html

4. Joliet Prison Interior -

Bryan, Miles. “You Can Now Tour The Old Joliet Prison (That One In ‘The Blues Brothers’).” WBEZ. WBEZ, June 8, 2018. https://www.wbez.org/shows/wbez-news/the-old-joliet-prison-is-back-in-business-for-tourists/676edfad-68d2-4907-9ff1-30a87f212dbe

5. Cook County Jail Brawl -

Lulay, Stephanie. “Cook County Jail Brawl, Stabbing Injures Five Inmates (VIDEO).” DNAinfo Chicago. DNAinfo Chicago, January 9, 2017. https://www.dnainfo.com/chicago/20170106/little-village/5-people-stabbed-cook-county-jail-fight/

6. Cook County Jail Unit -

Meisner, Jason, and Steve Schmadeke. “Lawsuit Accuses Cook County of Allowing ‘Sadistic Culture’ at Jail.” chicagotribune.com. Chicago Tribune, May 21, 2019. https://www.chicagotribune.com/news/breaking/chi-cook-county-jail-brutality-lawsuit-20140227-story.html

2. “An End to Mass Incarceration: University of Chicago.” SSA, January 1, 1970. https://ssa.uchicago.edu/ssa_magazine/end-mass-incarceration

3. Michaels, Samantha. “Chicago’s Jail Is One of the Country’s Biggest Mental Health Care Providers. Here’s a Look inside.” Mother Jones, January 11, 2019.

https://www.motherjones.com/crime-justice/2019/01/chicagos-jail-is-the-one-of-the-countys-biggest-mental-health-care-providers-heres-a-look-inside/

4. “Making the Case for Funding and Supporting Comprehensive, Evidence-Based Mental Health Services in Illinois.” illinoishealthmatter.org. NAMI Chicago, May 2015

5. “Black Holes of Architecture.” Chicago Underground Practice. Accessed September 19, 2019. http://www.chicagoundergroundpractice.com/black-holes-of-architecture.html

6. “Annual Determination of Average Cost of Incarceration.” Federal Register, April 30, 2018

7. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2018/04/30/2018-09062/annual-determination-of-average-cost-of-incarceration

8. “Cook County Jail’s History.” Cook County Sheriffs. Accessed September 19, 2019. https://www.cookcountysheriff.org/cook-county-department-of-corrections/cook-county-jails-history/

9. “Economic Perspectives on Incarceration and the Criminal Justice System: Executive Summary (Excerpted).” Federal Sentencing Reporter 28, no. 5 (January 2016): 361–62. https://doi.org/10.1525/fsr.2016.28.5.361

10 “COLLATERAL COSTS: Incarcerations Effect on Economic Mobility.” Accessed September 19, 2019. https://www.pewtrusts.org/~/media/legacy/uploadedfiles/pcs_assets/2010/collateralcosts1pdf.pdf

11. Travis, Jeremy, and Bruce Western. The Growth of Incarceration in the United States: Exploring Causes and Consequences. Washington, D.C.: The National Academies Press, 2014

12. James, Doris J., and Lauren E. Glaze. “Mental Health Problems of Prison and Jail Inmates.” PsycEXTRA Dataset, 2006. https://doi.org/10.1037/e557002006-001

13. “The Growth of Incarceration in the United States: Exploring Causes and Consequences.” Choice Reviews Online 52, no. 05 (2014). https://doi.org/10.5860/choice.185911.

14. John, Arit. “A Timeline of the Rise and Fall of ‘Tough on Crime’ Drug Sentencing.” The Atlantic. Atlantic Media Company, April 22, 2014. https://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2014/04/a-timeline-of-the-rise-and-fall-of-tough-on-crime-drug-sentencing/360983/

15. “Prison Health Care Costs and Quality.” The Pew Charitable Trusts. Accessed

September 12, 2019. https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/reports/2017/10/prison-health-care-costs-and-quality/target="_blank">www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/reports/2017/10/prison-health-care-costs-and-quality

16. September 12, 2019. https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/reports/2017/10/prison-health-care-costs-and-quality

17. Thompson, Christie. “Why So Few Federal Prisoners Get The Mental Health Care They Need.” The Marshall Project. The Marshall Project, November 21, 2018. https://www.themarshallproject.org/2018/11/21/treatment-denied-the-mental-health-crisis-in-federal-prisons.

18. “Top Adviser to Richard Nixon Admitted That ‘War on Drugs’ Was Policy Tool to Go After Anti-War Protesters and ‘Black People’.” Drug Policy Alliance. Accessed September 20, 2019. http://www.drugpolicy.org/press-release/2016/03/top-adviser-richard-nixon-admitted-war-drugs-was-policy-tool-go-after-anti

19. “Cracks in the System: 20 Years of the Unjust Federal Crack Cocaine Law.”

American Civil Liberties Union. Accessed September 20, 2019. https://www.aclu.org/other/cracks-system-20-years-unjust-federal-crack-cocaine-law

20. Barber, Judson. Interviewed by Juan Acosta

September 11th, 2019

21. “Timeline.” Old Joliet Prison. Accessed September 20, 2019. https://www.jolietprison.org/timeline/

22. Dodge, L. Mara. “Whores and Thieves of the Worst Kind” a Study of Women, Crime, and Prisons, 1835-2000. DeKalb: Northern Illinois University Press, 2006

23. “Cook County Jail’s History.” Cook County Sheriffs. Accessed September 19, 2019. https://www.cookcountysheriff.org/cook-county-department-of-corrections/cook-county-jails-history/

IMAGE CREDITS

1. Eastern State Pen Hallway -

“Timeline.” Eastern State Penitentiary Historic Site. Accessed September 20, 2019. https://www.easternstate.org/research/history-eastern-state/timeline

2. Eastern State Pen Cell -

“Eastern State Penitentiary.” Flashbak. Accessed September 20, 2019. https://flashbak.com/benjamin-franklin-forced-enlightenment-on-isolated-prisoners-inside-the-worlds-first-penitentiary-364464/12-cassidys-book-two-inmates-in-a-cell/

3. Joliet Prison Exterior -

Katelyn Oprondek Special to the Daily Journal. “Exhibit Explores What’s to Be Done with the Old Joliet Prison.” The Daily Journal, November 19, 2016. https://www.daily-journal.com/news/local/exhibit-explores-what-s-to-be-done-with-the-old/article_a4f34ffb-ea62-567d-86d9-7d2e257c336f.html

4. Joliet Prison Interior -

Bryan, Miles. “You Can Now Tour The Old Joliet Prison (That One In ‘The Blues Brothers’).” WBEZ. WBEZ, June 8, 2018. https://www.wbez.org/shows/wbez-news/the-old-joliet-prison-is-back-in-business-for-tourists/676edfad-68d2-4907-9ff1-30a87f212dbe

5. Cook County Jail Brawl -

Lulay, Stephanie. “Cook County Jail Brawl, Stabbing Injures Five Inmates (VIDEO).” DNAinfo Chicago. DNAinfo Chicago, January 9, 2017. https://www.dnainfo.com/chicago/20170106/little-village/5-people-stabbed-cook-county-jail-fight/

6. Cook County Jail Unit -

Meisner, Jason, and Steve Schmadeke. “Lawsuit Accuses Cook County of Allowing ‘Sadistic Culture’ at Jail.” chicagotribune.com. Chicago Tribune, May 21, 2019. https://www.chicagotribune.com/news/breaking/chi-cook-county-jail-brutality-lawsuit-20140227-story.html